Following the 1948 election of the South African National Party, South Africa became entrenched with oppression under the newly elected apartheid regime. This regime was characterized by the legal segregation of its citizens as an effort to solidify the country’s political power, as well as economic benefit. Motivated by the emerging injustices, an anti-apartheid movement spurred that fought to replace the legal systems with equality and to drive out the National Party.

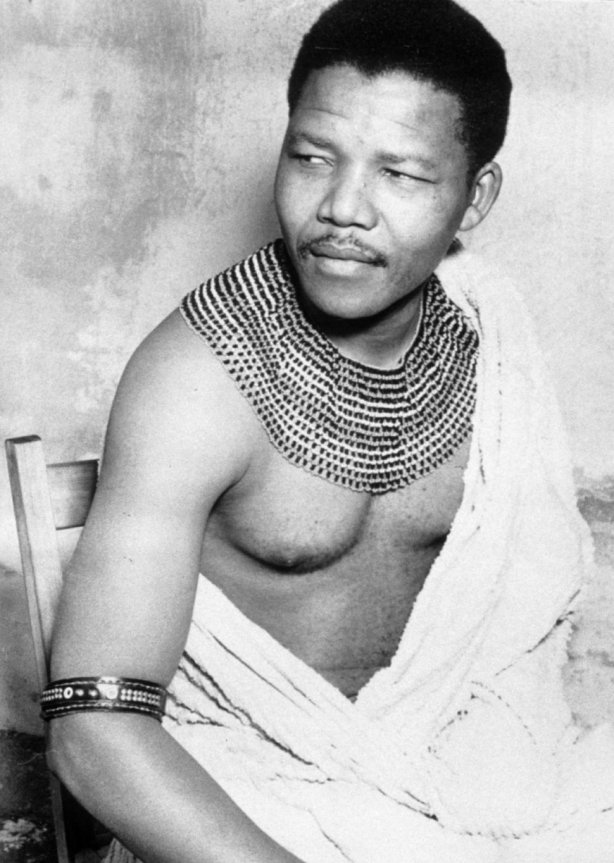

As one of the most significant anti-apartheid advocates in South African history, Mr. Nelson Mandela, born July 18th, 1918, played a major role in the development of the movement’s rhetoric. He now stands out as a global icon fighting for peace and equal rights for all. Central to Mandela’s argument against apartheid was that it directly violated the ideas of true democracy.

Directly following the rise of the National Party, the 1950’s were a time of active political participation for Mandela, most notably with the African National Congress (ANC). Drawing from Marxist theory, Mandela asserted ‘labor power’ as an tool of resistance against unjust laws during the Defiance Campaign of 1952, empowering the masses to recognize its natural power: “there is a mighty awakening among men and women of our country and the year 1952 stands out as the year of this upsurge of national consciousness”. The Defiance campaign was said to have awoke the “political functioning of the masses” (Mandela, 4). This evokes the memory of Fanon, who believed that, “The living expression of the nation is the collective consciousness in motion of the entire people. It is the enlightened and coherent praxis of the men and women” (Fanon, 144). By educating the masses to understand their potential efficacy, Mandela was able to incite national consciousness. Much later in 1964, Mandela goes on to further reflect Fanon’s notion of national consciousness as a source of motivation during his speech at the Rivonia trials: “I have done whatever I did, both as an individual and as a leader of my people, because of my experience in South Africa and my own proudly felt African background, and not because of what any outsider might have said.”

Opposed to the use of violence, Mandela spoke out against guerilla warfare. Instead, he believed in the power of democracy. Central to Mandela’s notion of democracy was the basic dignity of the individual, the right to a political consciousness. Among the many legal inequalities was denying the oppressed their language in schools, and instead replaced it with Afrikaans, the language of the oppressor. Fundamentally undemocratic, this inherently denied many people the opportunity to maintain tradition, which according to Mandel, is essential to the success of any democracy (Mandela, 19). Again, Mandela reflects the thinking of Fanon, who sees the imposition of language as part of the internalizing processes of decolonization; he also posits that the oppressor’s primary form of language is violence (Fanon). Soon enough, Mandela comes to discover this himself. After being arrested in 1956 for high treason, Mandela was subsequently acquitted. Then, in 1959, Parliament passes the Promotion of Bantu Self-Government Act, which forces the resettlement of blacks into eight separate “tribal homelands”, which the ANC adamantly opposes. Tensions rise as both the government and ANC refuse to concede in any way, leading to a culmination of pressure to act.

While Mandela’s approach to the anti-apartheid movement began with hopes of nonviolence, there came a point at which he ultimately recognized that this was futile after having exhausted all potentially peaceful and legal channels. By the beginning of the 1960’s, the ANC turned to force as the only apparent potential source of change, when on 69 are killed at Sharpeville for protesting the apartheid and the ANC is banned. In June 1961, Mandela described the limitations of legal struggle with the traditional proverb: “The attacks of the wild beast cannot be averted with only bare hands” (Boehmer, 109).

Faced with callous obstacles of colonization, racism, oppression, and dehumanization, Mandela’s turn to violence is reminiscent of the same logic used by Frantz Fanon, who believed in the use of violence as an inevitably necessary force in fighting for one’s freedom. He says, “The colonized man liberates himself in and through violence. This praxis enlightens the militant because it shows him the means to the end” (Fanon, 44). Similarly, Mandela speaks to this same kind of certainty, saying that not did the government policy make violence inevitable, but that “…there would be no way open to the African people to succeed in their struggle against the principle of white supremacy….only then did we answer violence with violence” (Mandela, 1964). This is also similar to the words of Malcolm X from his speech “After the Bombing”, in which he condones violence in the name of self-defense: “So I don’t believe in violence—that’s why I want to stop it. And you can’t stop it with love….So, we only mean vigorous action in self-defense, and that vigorous action we feel we’re justified in initiating by any means necessary” (Malcolm X, February 14, 1965).

Mandela’s beliefs of violence finally merged after the Sharpeville massacre with active efforts to liberate the masses when, in 1961, he left the country and went underground to organize an armed struggle. He and other ANC leaders formed Umkhonto we Sizwe (MK), a militant wing of the ANC. Beginning on December 16, 1961, MK, with Mandela as its commander in chief, launched bombing attacks on government targets and continued to make plans for guerilla warfare. Upon returning to South Africa, Mandela is arrested, convicted and sentenced to five years. While in prison, he is then brought to trial along with other ANC leaders and charged with sabotage and attempting to overthrow the government; they are sentenced to life in prison and sent to Robben Island in 1964 (PBS). In his speech before beginning his sentence, Mandela ends with this statement,

“During my lifetime I have dedicated myself to this struggle of the African people. I have fought against white domination, and I have fought against black domination. I have cherished the ideal of a democratic and free society in which all persons live together in harmony and with equal opportunities. It is an ideal which I hope to live for and to achieve. But if needs be, it is an ideal for which I am prepared to die.”

Mandela maintained his position while serving this sentence that he would rather sacrifice his right to freedom than condone the atrocities of the apartheid. Again, Mandela emulates the sentiment of Fanon who believes the “…spirit of self-sacrifice and devotion to the common interest fosters a reassuring national morale which restores man’s confidence in the destiny of the world and disarms the most reticent of observers” (Fanon, 56). And while Fanon speaks to a different type of self-sacrifice, that is, of labor, his words still carry the same predilection for commitment to equality and true democracy. Mandela’s willingness to sacrifice is a sure sign of his efficacy as a leader and an intellectual, in or out of prison. Mandela’s perseveres for a total of twenty-seven years, during which time the resistance escalates and violence continues. After the government declares a State of Emergency in response to widespread unrest in black townships, the government approaches Mandela for consultation. Ultimately, President Botha resigns and the new President F.W. de Klerk dismantles the apartheid structure in 1989; the ban is lifted from the ANC and Mandela is released from prison in 1990. Since then he has been rewarded the Nobel Peace Prize and has also been elected South Africa’s first black President (PBS).

Mandela’s sense of duty towards equality is reflected in his refusal to renounce armed struggle as a necessary means to freedom. His patience and openness for national reconciliation by the end of his term in prison is suggestive of a superior moral stature. While he was a very strong political activist, his philosophical legacy has made a significant impact on he intellectual tradition as a whole. And though his arrest and subsequent imprisonment might suggest a passive resistance, his enduring dedication to a just democracy is what classifies him as intellectual; he was willing to sacrifice everything he knew for something he had never even really experienced.